AI and the Future of Education in India: Insights from the Bengaluru Skill Summit 2025

Attending the Bengaluru Skill Summit 2025 gave me a front-line view of the issues facing India's future workforce. The round table discussions, which included key policymakers like Prof. Niranjana S.R. of the Karnataka State Higher Education Council, academic leaders like Dr. Sudhir Krishnaswamy of the National Law School of India University, and on-the-ground innovators like Fr. Deepak Joseph of St. Joseph's Institute of Skills, illuminated a core, systemic conflict: India is running on a dysfunctional two-track education system that fails to produce genuinely skilled, employable citizens.

The Core Conflict

This conflict is defined by two parallel systems that both promise to be the solution but miss the mark entirely.

1. The Idealization of Formal Education

On one hand, we have the formal university system that's idealized as the only way to be successful. This model arguably still functions for a privileged minority in Tier 1 institutions, where high-quality faculty, resources, and peer groups create an environment of competitive exposure.

For the vast majority of India, however, this has devolved into a societal race for marks and degrees that are increasingly disconnected from real-world capability.

This system is built to reward compliance and rote learning, not critical thinking or practical application.

2. The Unregulated "Skilling" Mirage

The second track is the market's "solution" to the first: a chaotic ecosystem of online skilling, dominated by platforms like Coursera and Udemy. This system is plagued by a different, but equally critical, set of flaws:

- Lack of Verifiability: These platforms are notoriously easy to bypass. A system that is generally unregulated and test-based, rather than project-based, is simple to cheat, especially in the age of AI. Certification is frequently gained without skilling, rendering the credentials themselves suspect.

- No Tangible Outcomes: These courses provide no tangible value beyond the skills a student picks up independently. They only reward those who are already effective, self-directed learners, failing the very students who need the most structural support.

- Credential Oversaturation: The industry is now so flooded with these "microcredentials" that they no longer signal competence. They merely indicate that a person had the free time to click through a series of quizzes.

The Failure of Formal Education is Being Accelerated by AI

This broken, two-track system is not just failing; it is being made obsolete by Generative AI.

The core vulnerability of this entire pedagogy is its reliance on information recall and standardized testing. This reliance on standardized testing is backed by decades of research and is often subject to rigorous compliance to ensure that it's really testing students' capabilities.

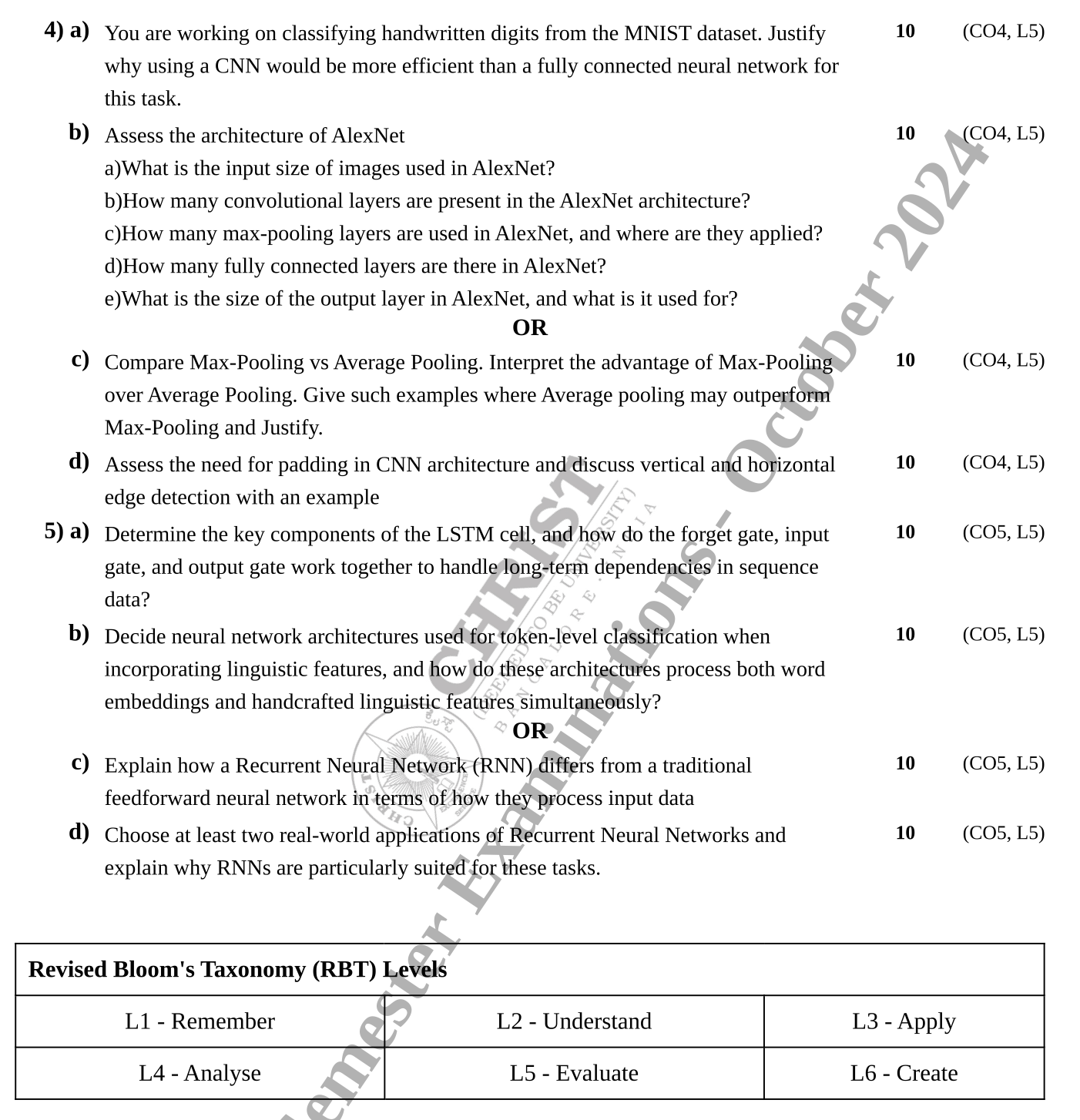

Exam questions often use "trigger words" from higher levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy (like "Assess" or "Decide") to sound more rigorous, even when they are actually testing lower-level cognitive skills like recall or basic comprehension.

My personal experience with this at Christ University

Christ University's question papers are mapped to higher Bloom's Taxonomy levels such as Analysis, Evaluation, and Creation to engage students' critical thinking and ability to create new information. This seems like a great idea on paper, but the reality is, to score higher marks, it's better to memorize the answers and information available on the slides/notes provided.

The best example of this is Question 4b in the Image below. Despite being tagged as an L5-Evaluate (look right) question with the trigger word 'Assess', the answer is a simple recall of the information available on the slides/notes provided.

Now at the end of the day, tasks that are heavy on information recall and basic understanding are the first to be automated by AI. These skills are no longer special or unique to humans and the market reflects that.

We can no longer afford to debate the issue; we must fundamentally change the educational pedagogy to make any real difference in how we teach and learn. The way we evaluate, test, and impart experience must be rebuilt from the ground up. The path forward is to build a more project-based, open-ended learning system—one that values the human-centric skills of critical thinking, problem-solving, and adaptability, which AI can augment but never replace.

The Incentive Mismatch: Why Skilling Fails

The failure of skilling and microcredentials is not just about bad courses; it is about a fundamental mismatch of incentives.

In many parts of India, especially in areas with low industry exposure, students are hyper-focused on academics. This is not a choice—it is a rational response to an environment where marks are the only visible, understandable metric for success. Skilling is considered a lower quality option, not a co-equal path. The direct result is low employability, even among high academic achievers.

The obsession with academics is reinforced by the idealization of white-collar jobs by both academia and the industry. They focus disproportionately on the roughly 10% of jobs that are "white-collar."

We are, in effect, designing an entire educational system that prepares 80% of our students for 10% of the available roles. This system actively ignores the concept of "skills for livelihood" and creates a massive, engineered gap, causing the other 70% to be unemployable through no fault of their own.

This misalignment is cemented by a societal perception gap. India has an informed but not knowledgeable society — one that is obsessed with the symbols of education (marks, degrees) rather than the substance (capability).

This focus on marks leads to the active dismissal of high-value, skill-based pathways. A diploma that offers direct employability is often viewed as "less than" a theoretical degree that offers none.

Academia vs. Industry: What's the Difference?

This leads to a core philosophical question:

Should universities even focus on industry, or are they meant for pure academia?

This is a false dichotomy. The goal of a university is not to be a trade school or an ivory tower. Its purpose is to produce capable, critical thinkers, and that requires blending both. As Dr. Shilpa Kalyan, Dean at Manipal Academy of Higher Education (MAHE) pointed out during the discussion, inter-departmental and inter-field education is precisely what makes graduates adaptable and employable. An engineer who cannot write a coherent proposal is as unemployable as a historian who cannot interpret data.

The Outdated Practitioner

The greatest barrier to this integration is often the faculty. For a university to succeed, its professors must be industry-connected practitioners, not just researchers teaching a decade-old curriculum.

My own experience at CHRIST University is a perfect case study. CHRIST is marketed as a placement-focused, industrially-connected institution. It has high expectations for students to build relevant, complex projects.

Yet, there is a fundamental disconnect. The curriculum often fails to provide the basic, non-negotiable skills required to build those very projects. Critical tools like Git for version control, familiarity with cloud providers like AWS or Azure, or even awareness of modern, job-relevant frameworks like LangChain are simply absent from the syllabus.

This creates a frustrating double standard. Students are expected to produce industry-level work while being taught by professors who, in many cases, are disconnected from the industry's ground reality and may not have built a real-world project in the last decade.

This obviously does not apply to all professors. Many, who I've had the pleasure of working with, such as Dr. Shubi K Mani and Kushal B S are competent and current. But the system itself does not incentivize or require faculty to remain practitioners, creating a gap that students are forced to bridge entirely on their own.

A New Pedagogy

If the old models are broken, what replaces them? The solution is not to build better-skilling tracks or slightly more relevant degrees.

The solution is to fundamentally shift the goal of education from credentialing to building competence.

The most compelling framework I heard came from Aromal Revi of the Indian Institute for Human Settlements (IIHS). It reframes the purpose of education entirely. Instead of focusing on content delivery, it proposes a three-stage "Problem-Solver Pipeline" that is designed to build capability, not just knowledge.

This pedagogy is built on a simple, sequential model:

- Learning: First, teach students how to learn. This foundational step is about building true general competence—the metacognitive ability to acquire new skills, discard old ones, and adapt to new challenges. This makes students lifelong, independent upskillers.

- Problem-Solving: Second, deploy that learning ability against real challenges. Students are not taught "skills" in a vacuum; they acquire them on the way to solving a complex, open-ended problem. This is true project-based learning, where the skill is a tool, not the end goal.

- Scaling: Finally, guide students in scaling their solutions. This stage provides critical support and mentorship, pushing them to move from a theoretical project to a real-world application, forcing them to confront the realities of implementation.

Reframing the Solution: From Degrees to Competence

Universities must focus on developing general competence. This is not just a vague "soft skill." It is the foundational, metacognitive ability to learn, unlearn, adapt, and apply knowledge to solve new problems. This competence is what makes a person employable for life, long after their specific technical skills, like a single coding language or framework, become obsolete.

In this model, skills are acquired as a necessary by-product of solving problems, not as academic modules increasingly disconnected from industry. This approach inherently requires project-based learning and industry-connected faculty to function. It moves evaluation from "Did you pass the test?" to "Did you solve the problem?"

This is not just speculative. Some of the leading institutions below have already adopted their own approach to solving this problem and they've largely succeeded.

Case Study: Olin College of Engineering (USA)

Olin's entire curriculum is project-based. It largely scraps traditional lectures and academic departments, forcing students to learn engineering by doing it.

Its flagship "SCOPE" program places multidisciplinary student teams with a corporate sponsor (e.g., Amazon Robotics, Pfizer) for a full academic year. Their job is to solve one, significant, real-world problem for that company.

Case Study: Drexel University (USA)

Drexel's model is built on Cooperative Education (Co-op). This is not just a summer internship; it is a core degree requirement.

Students alternate between six months of classroom study and six months of full-time, paid employment in their field. Students can graduate with up to 18 months of professional experience.

Nearly 48% of graduates receive a full-time job offer from one of their former co-op employers.

Case Study: MIT ADT University (India)

MIT ADT provides a strong Indian example, embedding industry linkage directly into its mandatory curriculum.

Project-based learning is required every semester, not just as a final-all capstone. The university operates a highly structured system with 200+ active industry mentors, and it mandates participation in hackathons and the publication of research papers for third year and final-year students.

This creates a high-output, high-pressure environment that forces students to build, document, and compete. It directly aligns their academic work with industry standards and practices.

These institutions prove that when you stop treating students as vessels for information and instead train them as general-purpose problem solvers, you create graduates who are not just "skilled," but truly competent.

The Student Perspective: Cognitive Offloading and the Dead Brain Loop

While policy is being debated by management, as a student, I can see (and have experienced) a more immediate existential crisis: cognitive offloading.

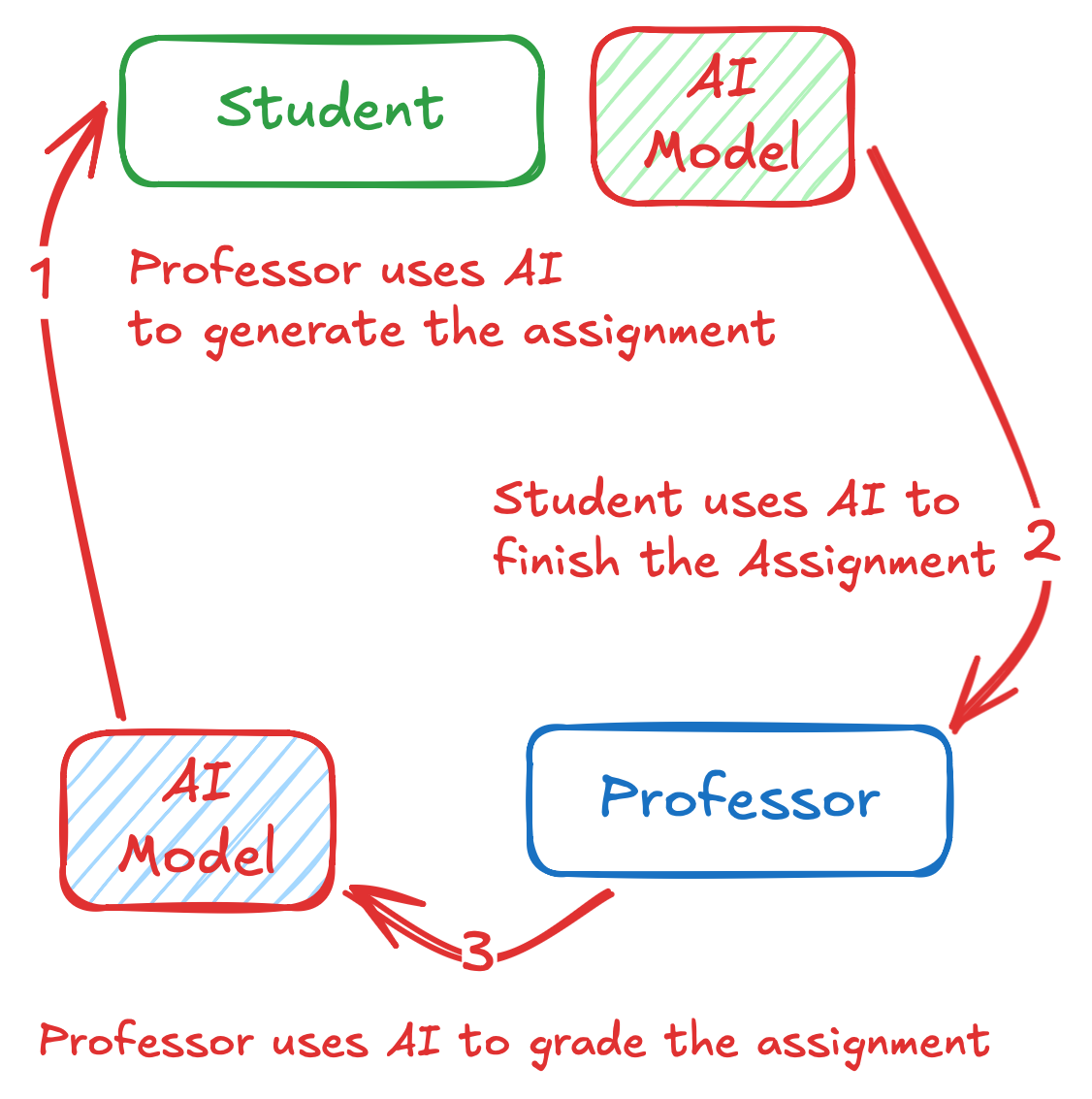

The greatest danger isn't that AI will take our jobs; it's that the current educational model encourages us to outsource our thinking before we even enter the workforce. Universities still rely on outdated assessment methods such as essays, assignments, and mini projects, which has created a "Dead Brain Loop":

With this cycle of every party in this situation offloading their work, there's no real learning or incentive to learn. Doing the assignments yourself will lead to lower scores if it's being scored by an AI. This creates a situation where you're actively being rewarded for not thinking.

Any assignment that can be fully done by AI with no effort required is now obsolete. We need to adopt and use open-ended, project / presentation based assignments that require students to at the very least learn. To combat this, core teaching and evaluation must shift immediately toward open-ended, project-based assessments, work that requires critical thinking, problem solving, and practical outcomes, which an LLM cannot fake.

Developing Metacognitive Literacy

The Dead Brain Loop persists because nobody in the cycle is actually thinking. The antidote is not to ban AI or return to pen-and-paper exams. It is to teach people how to think about their own thinking. As AI models become ubiquitous, the primary skill for students and professionals alike shifts from doing the task to managing the process. This requires Metacognitive Skills, the ability to monitor and control one's own thought processes.

Effective AI interaction is an exercise in higher-order thinking. When interacting with an LLM, you are no longer just a creator; you are a manager. You must clearly formulate goals, decompose complex problems into communicable sub-tasks, and—most critically—possess the self-awareness to evaluate the output with well-adjusted confidence.

A manager needs to clearly understand and formulate their goals, break down those goals into communicable tasks, confidently assess the quality of the team’s output, and adjust plans accordingly along the way. Moreover, they need to decide whether, when, and how to delegate tasks in the first place. Among others, these responsibilities involve the metacognitive monitoring and control of one’s thought processes and behaviour.

Without these skills, users fall into the trap of accepting plausible-sounding but incorrect AI outputs simply because they were generated quickly. This lack of feedback in Generative AI creates a challenging environment where self-monitoring is the only safety net.

To be genuinely competent in this new era, we must focus on developing metacognitive literacy. This means knowing not just what to ask, but how to evaluate the validity of the answer. We must maintain a critical distance from the machine, ensuring that human judgment remains the architect of the workflow, while AI serves merely as the builder.

So, What Now?

The old educational model was built on a university's monopoly on information. It showed its cracks in the age of information, with the internet making this information free and accessible to all. Public archives like Anna's Archive and Sci-Hub allowed anyone to access the resources that were only available via universities before. That monopoly is gone forever. In an age where an LLM can generate the answers to every test assignment and exam assigned in a student's course in a matter of minutes, we must seriously revisit the skills and competencies that we're teaching our youth.

The Bengaluru Skill Summit brought the right people together, policymakers, academic leaders, and industry heads, but summits don't change systems. People do. Stop waiting for your university to catch up. Build projects that solve real problems, learn how to learn, and develop the metacognitive awareness to know what you don't know.

The institutions that will matter in the next decade are the ones that produce problem solvers, not certificate holders. The future belongs to those who can learn, solve, and scale.

References

[1] CHRIST (Deemed to be University), Bengaluru - 560029. End Semester Examinations - October 2024. Bachelor of Technology SEMESTER - VII. Course Code: AIML735P. Course Name: NEURAL NETWORK. Syllabus Year: 2024-2025. https://www.christuniversity.in/